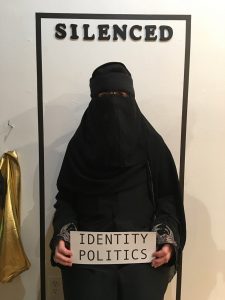

Woman in abaya at November 4, 2017, Opening reception of Silent. Silence. Silenced.

For the Silent. Silence. Silenced exhibit at Atlantic works, I showed a grouping of black & white monoprints of hooded heads that many gallery visitors said were fascinating. At the artist talk, one of the guests thought the row of prints reminded her of Crusaders.

It was a long haul through self-censorship for me to show the monoprints, because more than one of my yoga associates told me they would not come to the exhibit or send any students to the exhibit to see the hooded images because they were too ISIS and too upsetting.

Up until those conversations, with people I admire and am grateful to have in my life, it hadn’t occurred to me that I ought to sequester the images so the public would have a choice of whether or not to look at them. But I began to silence myself. Self-censor. Maybe I shouldn’t show them. Maybe the black hooded heads would upset people. Maybe I would be perceived as politically incorrect or a racist.

B & W monoprint

Consequently, as a way of working out my artistic dilemma, I made gold hooded heads and called them “Silenced by Capitalism.” For some reason, I was sure the concept and the sculptures of female heads tightly shrouded in gold would not be upsetting to anyone.

More conversations. With Charlene Liska who said “Don’t self-censor.” In conversation with fellow artist Brenda Star who said, “Art is supposed to get people to think about what’s going on, around them. How are people going to become aware if they are protected from images, from art?”

Art is always a process. Often I know what I am thinking about when I work. I know how I started thinking and when I finish I know more about what I am thinking.

This is the story of the monoprints:

Christine Palamidessi printing Black Hooded mono prints.

In the winter of 2017 I was artist in residence at Mass MoCA in North Adams, working on the printing press at Maker’s Mill. I was doing mono prints of the head of the Greek Goddess Nike, the image being based on the 420 BC bronze head of the goddess (now viewable in Athen’s Agora Museum). I thought I was exploring the imprints of antiquity on modern life and the meaning behind the Goddess: from the Victorious Female who rode in the chariot next to Zeus to a word and a swish on a sneaker. In addition I was exploring the meaning and hallucination that goes along with looking at a ‘head,” particularly the image of the first head we humans see and become visually attached to—the head of the mother who looks over the infant.

On the second or third day, I turned onn the radio. Our U.S. Senate had gathered to discuss Trump’s attorney general pick, Jeff Sessions. As I inked and pressed, Senator Elizabeth Warren read a letter, written by Martin Luther King Jr’s widow Coretta Scott King. The letter detailed Session’s history of racism and civil rights violations. The Speaker of the House shut Warren down; the Senate voted to silence her.

Silenced by Identity Politics

That was truly upsetting new for me. I dropped a black inked hood over the face of Nike; and I kept going. A portion of the monoprints, made when the artist was upset about a silenced woman, are on exhibit at SILENT. SILENCE. SILENCED. at Atlantic Works Gallery .

This is the process. We use our skills, our sensitivity, our history, our bodies. and react to social, political and aesthetic conditions in our environment.

The black, hooded icon consumed my work for several days, initially expressing censorship; female censorship; and then moving on to reference images of racism, terrorism, and public degradation, execution, religion, and war as realized by a simple, stark, isolated hooded black face.

A hood/sack placed over a human head silences; humiliates; deprives a person of soul and individuality, while at the same time identifies that person as a single member of an oppressed group exploited by those more powerful.

I began thinking of a Female Goddess, Victory, who then became Silenced, who then became a an meditative icon. An image is in effect in service to power. No one has ever cut off your head or mine. You are like me: a human being who speaks, an artist.