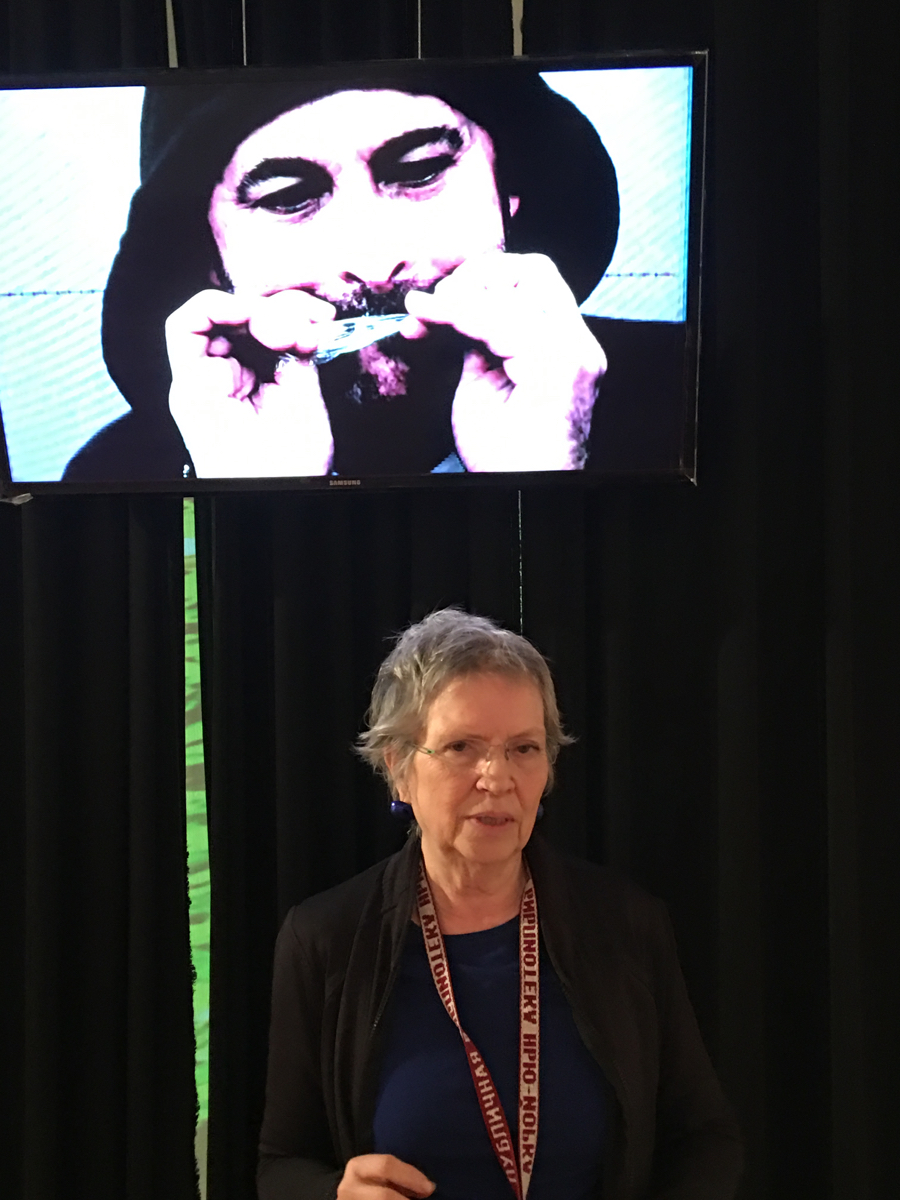

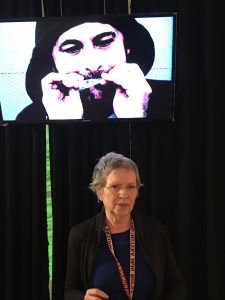

In the gallery with Charlene Liska, 2017

In the Silent. Silence. Silenced. exhibit at Atlantic Works Gallery, Charlene Liska sets up a Plato’s Cave, of sorts, using video and installation. Gallery visitors can see faces of the artist’s tribe on one screen and hear the echos of what they are saying–via deliberate use of headphone assistance– on a second screen in a different location in the gallery. At the same time the sound of silence–rather, what Liska offers as silence–is a bird’s chirping which permeates the gallery’s audio atmosphere. What the gallery-goer does not immediately realize: the bird chirping is mimicry of the real thing; a sound made by Liska’s Brazilian electrician, Elson.

Using the concept of Silence as the springboard, Liska plays with the possibilities of form and organization, flat planes, shadows, dimension and her own wit, imagination and experience.

“I see Silence as having two sides,” she says. “There’s the beautiful, spiritual and eternal. We are all seeking that and desperately want that kind of silence. And then there is the psychological side.

“Psychologically we’re all being silenced by too much noise. Too much data. It’s flooding in on us constantly.”

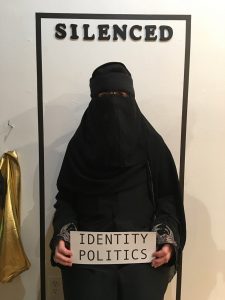

Artist Charlene Liska and her ‘Diorama’ installation at Silent. Silence. Silenced exhibit November 2107.

The far-side of the gallery houses her curtained-off installation Diorama. Liska creates a layered and a sculptural space that features her own image–talking but without sound–captured within a very small 3-d TV that hangs about six feet above the floor. A projection of a green shrub and brick wall hit and flash on the monitor. The green and red images reach back further, to the flat wall which is about 6 feet behind the suspended TV. The green flashes, changing shape, morphs. In the upper left corner, is a video cameo of a Boreal Warbler that seemingly watches over the pulsing installation.

“I have tremendous sensitivity to flashing light,” Liska said. “I suffer seizures. Epilepsy.”

Liska explains that epilepsy was a cruel condition to have as a child because it made her feel alienated, self-vigliant and hypersensitive. “Beginning when I was about 13, going on through menopause–estrogen can push you over the edge!”

She hid the condition. In high school teachers and administrators threatened ‘if you have another one’ they would have to put her in an institution. “That meant insane asylum,” she adds. Her family felt strongly that she and they should not talk about her condition publicly.

“I don’t stay silent about it anymore, or hide it.” Liska explains. The episodes and experience certainly influenced her art.

For example, waking up from a seizure Liska would see heads hovering above her. “Heads similar to the heads in my video interviews.” Of course the heads were her husband’s and daughter’s; earlier on her family’s.

Liska has shot many ‘head-on interviews.’

“I did one on Occupy Boston. Another in Berlin on the Documenta. The first video I made was with Anna [Salmeron]. We interviewed gay people about their first kiss. It’s titled ‘Crush’.”

She laughs. “I’m attracted to people’s heads and what’s going on in there.”

In the Silent. Silence. Silenced video Prophecy I, Liska interviews and celebrates her tribe of Atlantic Works Gallery artists. She requested the interviewees wear hoodies, a form of silencing, and asked them about the future.”What do you think it will be like?” But you can’t hear the answers, unless you walk to the other side of the gallery, to Prophecy II, and put on headphones, or read the text pinned to an opposite wall. Gallery-goers, however, can see the deconstructed pulse of the language, like a line of a heart monitor, that captures the sound waves of the interviewees answers. “It’s media chaos,” she says about the separation of voice from image. “It’s taken for granted in our world, words can easily be drowned and depersonalized in data.”

In the back nook of the gallery, Liska’s 12- hour video, Border Night not only pays homage to the past–early video artist Andy Warhol– but also to current and future questions regarding privacy and surveillance.

“I wanted to grab the opportunity to make this video before everything on East Boston’s waterfront changes,” Liska says. So, one night in September 2017, Liska set up cameras in her Border Street studio window and shot a dusk to dawn look at East Boston’s waterfront.

In addition, at the Silent, Silence Silenced exhibit, Liska shows archival prints: Newfoundland Bogs (from her time in Canada); Convent, Ghent; and Mojave Whistlestop.

Atlantic Works Gallery artist Charlene Liska in front of “Prophecy I Machine Transcription”: video, 2017 (image on screen is Elson, the Bird Caller)

There is not complete Silence in the gallery. We hear bird noises. “So many people associate silence to birdcalls,” Liska says. So she came up with bird sounds–a witty twistaroonee, of course: sounds made by her Brazilian electrician who has a knack for imitating and relating to birds. “They talk to him. He talks to them,” she says.

“When you go into the countryside to record silence, you get birdcalls. Even when you are not looking for them, there they are. It’s like birds live in a parallel universe. Their spirits fly and they don’t care what we do. They just go on and on. Unaffected.” She nods. “Birds are stronger than we are.”

Finally, going back to Platos Cave: the ‘prisoners’ in the cave perceived only shadows and echoes of real objects and were completely unaware that those forms were not the real thing. Ultimately, according to Plato, their perception was not false; by their understanding of the world, the shadows and echoes were the actual forms, since this was all they knew.

In ‘Liska’s Cave’, an ode to Silence, the world’s transition to a socially connected, digital society—the age of the internet–nudges the viewer to contemplate modern reality, and the shadows it casts on form. Here, in the gallery, the major form is video screens. And use of the form questions the separation of words from their speaker, the transformation of spoken text into paper flatness; the absence and ability to inject new words within the movement of a silenced mouth; and even the manipulation of self presentation.

In the gallery with Charlene Liska, 2017

“I do art because I like to do it,” Liska said. “I make art to make art, for no other reason.”

We can think of Liska as the bird in the corner of the gallery in Silent. Silence. Silenced. watching over the video screens. The sound of her voice has cast strong shadows that challenge our questions about the future and what we might choose to make or take from the video screen.